Famous composers and their approaches to rubato

We’ve already talked a little bit about Chopin, and his particular penchant for rubato in the right hand melody only, while keeping the accompaniment strictly in time. Each composer approached rubato differently, and when playing their pieces, although your interpretation may be different, I still think you should know how the composer felt about rubato when they composed the piece – their intention, if you like.

Bach

Bach came in a time when “rubato” as a concept did not really exist. Anybody who did not stick meticulously to the tempo was branded a bad player, incapable of even keeping basic tempo. However, Bach’s idea of “rubato” is often imprinted in his pieces, in the form of ornaments, such as trills and tremolos. Although these trills and tremolos are strictly timed, their function was similar to today’s rubato – to slow or speed a note.

Here’s what he himself said about rubato:

Mozart

Mozart, even in passages marked with passion and expressivity, almost religiously kept time. He said himself that time is “the most indispensable, hardest and principal thing in music”. He too, like Bach, came at a time before our modern day definition of rubato was widely accepted, or even known.

Beethoven

Beethoven is a bit tricky. It’s not quite as simple as “he did use rubato” or “he did not use rubato”. There are many accounts of him using rubato, especially in his conducting – it is reported that he often discussed tempo rubato in orchestral music with individual wind players, and Ignaz von Seyfred said that Beethoven’s conducting, in the early 1800s, had an “exactness with respect to expression” including “an effective tempo rubato“.

Beethoven’s earlier sonatas contained far fewer tempo altercations than this later ones, yet even his Op 1 and 2 sonatas contained more markings than any of Mozart’s sonatas. Many of his earlier sonatas did not indicate any tempo change at all, apart from the occasional ritardando or stringendo, but the use of fermatas over certain crucial notes joining movements and sections suggest that he wanted some flexibility in the playing.

Starting from Op 31, however, Beethoven begins to include far more tempo markings into this music, including accelerando, rallentando, poco ritardando, more fermatas, etc.

Ferdinand Ries described his own teacher’s playing with:

In Beethoven – An Introduction to His Piano Works, Dr Palmer writes in the introduction:

So basically, from all this, I gather that Beethoven used rubato himself, and probably intended for his pieces to have rubato, but I would warn against playing any of his pieces with anything more than a slight hint of it, unless you’re completely sure of what you’re doing, and have your heart entirely set on doing so.

Liszt

Like nearly all Romantic composers, Liszt loved rubato and put tempo changes in everywhere. Use it.

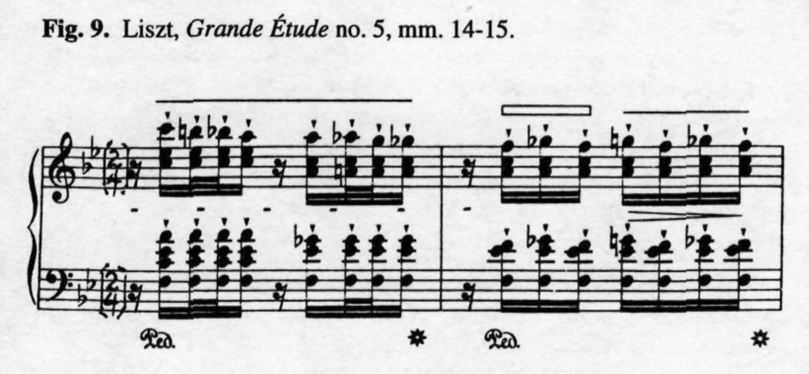

If you really want to read more about Liszt and rubato, here’s a short excerpt from The Uses of Rubato in Music, Eighteenth to Twentieth Centuries, by Sandra P. Rosenblum:

Long dash = rallentando, small box = accelerando

Long dash = rallentando, small box = accelerando

Summary of the above paragraph: Liszt loved tempo markings so much that he created his own shortcuts to write them faster. Use rubato.

Шопен

Фредерик Шопен (1810–1849) написал термин rubato в четырнадцати различных произведениях. Все места, отмеченные рубато в его четырнадцати композициях, имеют плавную мелодию в правой руке и несколько сопровождающих нот в левой руке. Таким образом, к рубато Шопена можно подходить с задержкой или опережением этих нот мелодии. Согласно описаниям игры Шопена, он играл мелодией, слегка задерживая или взволнованно предвкушая ритм, в то время как левый аккомпанемент продолжал играть вовремя.

Обычно использование им термина рубато в партитуре дает кратковременный эффект. Однако когда был отмечен термин semper rubato , он указывал на рубато, продолжающееся около двух тактов. Интересно, что Шопен никогда не отличался темпом после рубато. Это оставляет продолжительность «мгновенного эффекта» на усмотрение исполнителя. Следовательно, исполнитель должен понимать цель, по которой указывается рубато у композитора.

Слово rubato в своих композициях используется Шопеном по трем причинам : чтобы сформулировать повторение, подчеркнуть выразительную кульминацию или апподжиатуру и задать определенное настроение в начале произведения.

Первая основная цель, для которой Шопен отмечает rubato, — это артикуляция повторения музыкальной единицы. Например, рубато, отмеченное в такте 9 в Mazurka Op. 6 № 1 указывает на начало повторения после первой восьмерки. Другой пример использования рубато встречается в Mazurka Op. 7 No. 3. В этой пьесе тема начинается с такта 9 и повторяется в такте 17, где отмечается рубато. Исходя из этого, исполнителю дается сигнал подойти к повторяющемуся материалу иначе, когда он повторяется во второй раз.

Ф. Шопен, Мазурка соч. 6 No. 1 bar 9-10, Oeuvres complete de Frédéric Chopin, Band 1, Bote & Bock, 1880 г., изображение из imslp.

Вторая основная цель Шопена в использовании рубато — создать очень выразительный момент, например, в высшей точке мелодической линии или в апподжиатуре. Например, в Ноктюрне соч. 9 № 2, такт 26 имеет интенсивно поющий момент, когда мелодия переходит в ми-бемоль. Однако эта ми-бемоль не самая высокая точка фразы. Поэтому Шопен отметил « poco rubato», чтобы показать исполнителю, что он может подчеркнуть чрезвычайно выразительный момент, но также сдержать фактический кульминационный момент, наступающий на один такт позже. Второй пример использования рубато во время пения — в его Втором фортепианном концерте. В подобной ситуации мелодия перескакивает до трех, сыгранных подряд ля-бемоль, и отметка «рубато» говорит исполнителю исполнять их в певческом качестве.

Ф. Шопен, Ноктюрн соч. 9 No. 2, Sämtliche Pianoforte-Werke, Band I, CFPeters, 1905, image form imslp.

Шопен в первую очередь отмечает рубато, чтобы подчеркнуть выразительные мелодические линии или повторение. Однако в некоторых случаях он также использует рубато, чтобы создать определенное настроение в начале произведения. Ноктюрн соч. 15 № 3 — один из примеров использования рубато для создания настроения. В ноктюрне соч. 15 № 3, Шопен отметил в первом такте « Languido e rubato» , как общее предложение всеобъемлющего способа подачи произведения. Вялое рубато влияет на темп, цвет тона, прикосновение и динамику, которые влияют на исполнителей, чтобы задавать настроение в начале произведения.

Ф. Шопен, Ноктюрн, соч. 15 № 3, Klavierwerke. Поучительное Осгабе, Том V: Ноктюрны, Schlesinger’sche Buch-und Musikhandlung, 1881, изображение из imslp

What should rubato feel like?

William B Yeats, one of the greatest poets the world has ever seen, said the following sentence in his poem “Adam’s Curse”:

In the same train of thought, rubato is difficult to pull off because although it should sound spontaneous – after all, that’s the point of it; as if the player has simply sat down and is changing the tempo as they feel the music needs to be expressed – it needs to be meticulously prepared. The key to rubato is actually sitting down and writing in, or perhaps highlighting sections that you think should be sped up and sections that you think should be slowed down.

One of the best ways to determine where to put rubato and how to implement it is to sing the melody line – do it in the shower! Try to remember where the rhythm naturally falls and later duplicate it in your playing.

At its very core, rubato is designed to create tension, and then release, sort like stretching an elastic band and letting it go. By delaying resolution, or delaying the momentum of the song, we heighten expectation, before quickly “catching up” in a movement that should feel like watching the tides at the beach.

Above all, remember that rubato is nothing more than an ornament – a flourish on the piece of music, in the same way a candy flower is a flourish to a cake. Never let the rubato take over, or control the piece of music. Rubato and pulse must not fight each other, they are not enemies. Quite the opposite. Rubato works to enhance the pulse of the piece, yet the pulse must always be clear, in order to bring out the best in the rubato.

Types of rubato

There are two kinds of rubato – one where the accompaniment is kept in strict metronome timing and the melody is altered, and one where both are changed by the rubato.

When playing Chopin, while many people argue that Chopin must be played with a both melody + accompaniment rubato, in Carl Mikuli’s Chopin as Pianist and Teacher (he was a student of Chopin’s), he writes this of the man himself:

Henry T. Finck’s Success in Music and How It Is Won also talks much about Chopin, and says that he repeatedly drilled into his students the important of keeping them in the left hand.

Others condemn this approach and liken it to a singer soaring expressively while their accompaniment bangs away monotonously at one rhythm (Constantin von Sternberg did so in his Tempo Rubato, and other essays).

However, in terms of interpretation and taste, it all comes down to preference. Personally, I play Chopin pieces how Chopin played them because that’s probably how he wanted them played.

So what does “tempo rubato” mean?

The dictionary says that rubato is:

but that doesn’t really mean anything to me. Let’s go a bit further.

Rubato comes from the Italian word “rubato” (surprise!) which means robbed. This, in turn, comes from the Medieval Latin term “raubare” meaning “to rob” (again, surprise!). Together with “tempo”, we get “tempo rubato”, or robbed time.

One of the very fundamental beginner mistakes when it comes to rubato, and one especially seen when students are just beginning to experiment with a freedom of rhythm, is the often over exaggerated and over indulgent exaggerations of it. See, for example, any beginner rendition of Clair de Lune or the Moonlight Sonata.

The concept behind rubato is one of borrowing time, not creating or destroying it. Thus, when a piece speeds up at the beginning, the general expectation is that it will slow down later on – hence the “robbing” of the time from that passage later on, to be used now. The idea behind rubato is that a 3 minutes piece without rubato should still be 3 minutes with it.

Daniel Barenboim explained it by saying that “tempo rubato means to “steal” time, and since we’re ethical people, we give back whatever we steal”. (Courtesy of Albert Frantz over at Key Notes).

A dictionary of foreign musical terms and handbook of orchestral instruments by Tom S. Wotton defines rubato as:

Many beginners often attempt rubato but end up with ad libitum, Latin for “at leisure”, or playing the passage at no real set metronome timing.

Неверные толкования

Определения музыкальных понятий (например, рубато) вызывают неправильное толкование, если они игнорируют художественное музыкальное выражение. Тип рубато с регулярным аккомпанементом не требует абсолютной регулярности; аккомпанемент по-прежнему полностью учитывает мелодию (часто певца или солиста) и при необходимости меняет темп:

В музыке Шопена слово «rubato» встречается всего в 14 его произведениях

В то время как другие композиторы (такие как Шуман и Малер) игнорируются, когда мы подходим к этому вопросу, мы часто не принимаем во внимание немецкие термины, такие как «Zeit lassen», для того же принципа. Тот факт, что «rubato» — это скорее аспект исполнения, чем просто композиционный прием, заставляет нас обратить свой взор на другие термины, которые можно интерпретировать как искажения темпа, такие как «cedéz», «espressivo», «calando», «incalzando»

«, или даже особая» сладость «Брахма, столь же ясны в исполнении.

Where to use rubato

- A change in harmony or mood

A change in key, or an unexpectedly dissonant note can often be delayed – kind of like the hush of the crowd before the fall of an executioner’s blade. Rubato here is used to hint at the change to come and then when it does come, heighten drama.

- Long, slow, “stretchy” pieces

Slow pieces with long, slow melodies such as Chopin’s Funeral March can get, quite simply, boring and monotonous without rubato, as the accompaniment is often the same for the entire piece. Rubato allows the player to make the piece interesting. When playing melodies for pieces like this, I find it useful to try and keep in my mind an image of stretching bubble gum. Barenboim does a fantastic rendition of the second movement of Beethoven’s Pathetique below.

- The ending of a phrase

The ending of a phrase is often very satisfying, as the key commonly resolves to the very first scale degree – the tonic key, which is the most stable and (I would say) most satisfying note in a scale. Delaying the resolution notifies the audience of a phrase ending, and often allows them to prepare for another section, or to applause.

- Resolution to a grounded scale degree

In a scale, there are three notes that are particularly “magnetic” – they are the most stable in the scale. These notes are the first note (the tonic), the fifth note (the dominant) and the third (the median). In the C Major scale, for example, this is C, G and E. All other notes tend to be “drawn” to these notes for a sense of resolution – 2 wants to do to 1, 4 wants to go to 3, 6 wants to go to 5 and 7 wants to go up to 8, or 1. For example, listen to the incomplete scale of C major below.

Notice how you are expecting the final note to play. In the same sense, when the melody goes to a 2, 4, 6 or 7, with the intention of then going to the tonic, dominant or median, slow down the resolution! Listen to the scale below, with a slight speed up and then delay before going to 8.

The rubato is exaggerated but you get the point. It’s satisfying, isn’t it!

- “Reaching” to a note, particularly octaves

The piano is a tuned instrument – you press a key and a pre-set sound comes out. This is in comparison to, say, the violin, where you can press in between a key and get an off-tune sound. Violins, often when going from one note to another, like to slide along that note – the same for singers. You’ll notice that singers, even pop singers, will slide to a note, rather than going straight to it.

Unfortunately, we can’t do that on the piano, and so the second best thing we can do is delay the note, to create a sense of reaching to the note. This is particularly useful for octaves, or any sort of big leap, because it creates the sense of soaring, the feeling of height and flying towards the note. Listen to Chopin’s Nocturne No 2, Op 9 below, and note the “reaching” for the octave notes.